After its relative lenient, “intelligent lockdown” approach to the COVID-19 coronavirus, the Netherlands has continued a singular trajectory in combating the pandemic. After its mitigation measures were loosened in May and June, the month of July introduced further changes – by re-opening fitness centers, relaxing prior restrictions on attendance for indoor and outdoor events (to maximally 100 and 250 people, respectively), and even abolishing restrictions in many public places (e.g., shops, museums, zoos, restaurants). In order to ensure that the virus continues to be contained, it is essential that Dutch citizens continue to comply with safe-distance measures (i.e., keeping a distance of 1,5 meters or more from others). However, the month of July also saw heated debate over the need for, and legitimacy of such mitigation measures, and furthermore, heralded a resurge of the number of infections. As such, it is crucial to understand to what extent Dutch citizens complied with safe-distance measures during the month of July, and which processes influenced them to do so (or not). To study these questions, we complemented our prior surveys in May and June with two additional waves, collected in early (7-10) and late (21-23) July. In this blogpost, we outline the results.

The June survey indicated that Dutch citizens’ compliance with safe-distance measures was eroding, as were many of the resources that sustained it. They reported lower practical capacity to comply, but also perceived the virus as less threatening, and reported lower substantive support for mitigation measures. Furthermore, they indicated that perceived social norms for compliance were waning. These processes may reflect the number of infections at that time, which had strongly reduced relative to their peak in March and April. Here, we examine how these trends have developed during the month of July, where more of the prior restrictions were lifted, but COVID-19 infection rates ceased to decline.

Evolution of compliance in the month of July

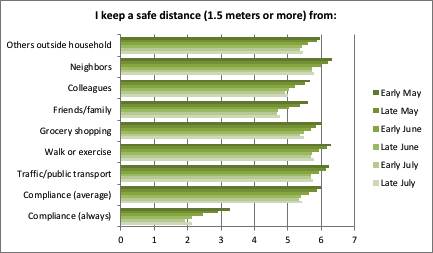

We conducted two surveys in representative samples of Dutch citizens, collected via the research panel StemPunt.nu. The first survey (N = 1064) was conducted between July 7-10, the second (N = 1023) between July 21-23. Survey participants were asked to what extent they kept a safe distance (1.5 meters or more) from others (1 = “never”, 7 = “always”) in various situations (e.g., in interactions with people from outside of their household, from colleagues at work, when walking or exercising, while grocery shopping, etc.). We compared reported compliance across these situations from early May to late July.

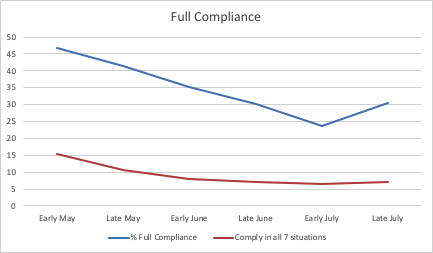

From early May to early July, a significant decline in the degree of self-reported compliance was observed. This was the case in all seven situations, as well as for compliance in general (i.e., averaged across all seven situations), and for the frequency of full compliance with the rules (i.e., the number of times that participants indicate that they “always” comply with the rules in each of the seven situations). However, by late July, this decline seemed to halt, and average compliance among Dutch citizens recovered to the level that was observed at the end of June. In percentages, the number of people who indicate that they always comply declined from an average of 46.7% (across all seven situations) to 23.5% by early July, but then recovered to 30.4% by late July. When considering the number of persons who always complied in all seven situations, this declined from 15.3% to 6.6% in early July, and recovered to 7.2% by late July.

Development of resources for compliance, early May-late July

Our previous surveys on May and June revealed several resources that enabled Dutch citizens to comply more with COVID-19 mitigation measures. To begin with, people complied more if they had greater practical capacity to keep at a safe distance from others, and when they perceived that others in their social environment engaged in social distancing. Also, there were some indications that they complied more when they regarded the measures as more clear, and were presented with fewer opportunities for violating them. How have these resources evolved during the month of July?

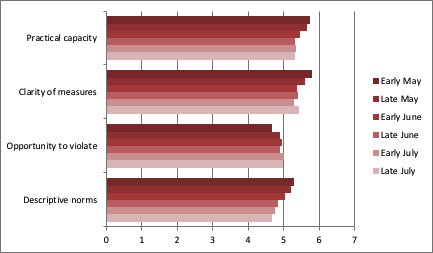

Relative to May, Dutch citizens’ practical capacity to comply had declined significantly in June. But compared to the level in late June, their capacity to comply did not decline further in July. A similar picture emerged for their perceptions of the clarity of the mitigation measures. These had also declined from May to June, and had continued to decline significantly at the start of July. But by the end of July, Dutch citizens’ perceptions of the clarity of the measures were no longer decreasing, and had partially recovered (to the level of late June).

In terms of the opportunities that they saw for violating safe-distance measures, these did not seem to increase further during the month of July. However, although other resources ceased to decline or partially recovered, perceived social norms for compliance continued to decline in July. So, even though their own practical capacity to obey the measures seems to have improved, Dutch citizens feel that social norms toward compliance are continuing to wane.

Our previous surveys further indicated that people who agreed more with safe-distance measures complied more, as did people who generally comply more with legal rules. How did these resources evolve in July?

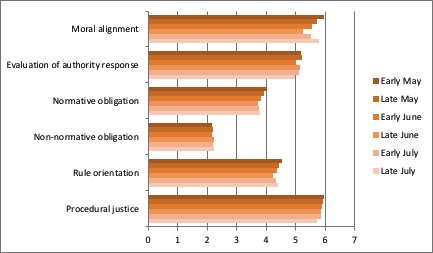

From May to June, Dutch citizens’ moral belief that people should keep a safe distance from others (moral alignment) had decreased significantly. During the month of July, however, their moral alignment with the measures showed a significant recovery. This also applied for the moral obligation that they themselves experienced to (unquestioningly) obey the authorities handling the Coronavirus: this normative obligation also ceased to decline from June to July – and indeed, by late July, was significantly higher again than it had been in late June. This pattern extended to the obligation that they felt to obey legal rules in general (rule orientation): this obligation also had decreased from May to June, but by late July had recovered significantly, to a level that was significantly higher than in late June. In sum, these results suggest that although substantive support for safe-distance measures among Dutch citizens had been falling from May to June, this has recovered in part during the month of July.

It is noteworthy, however, that perceptions of the authority response to COVID-19 seemed to decline somewhat during this period. Towards the end of July, participants evaluated the authority’s response to the virus as less adequate and consistent, and the enforcement of the measures as less procedurally fair. Possibly, these findings reflect the considerable regional differences in enforcement that were exposed during this period.

From May to June, we also observed that perceptions of the benefits of complying with safe-distance measures (but not the costs) influenced compliance. How did these resources develop during the month of July?

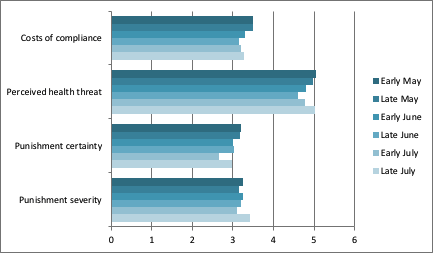

From May to June, perceptions of the health threat of COVID-19 had declined significantly among Dutch citizens, as had their perceptions of the costs associated with violating the rules (particularly the perceived likelihood of being punished for doing so). At the same time, their personal costs of complying with the mitigation measures (e.g., loss of income, ability to work as effectively as normal, etc.) had also declined. During the month of July, the perceived health threat of COVID-19 increased significantly again, and by the end of July had recovered to the level of early May. With regard to the personal cost of complying, this ceased to decrease during this period: complying with mitigation measures therefore was no longer getting cheaper for Dutch citizens in the month of July. Indeed, with regard to perceptions of the costs of violating the rules, these in fact had increased significantly by the end of July (relative to early July). This again may reflect the insights on the strictness of enforcement that became public during this period. Taken together, these results suggest that the perceived benefits of complying were increasing again during the month of July, after their earlier decline during the months of May and June.

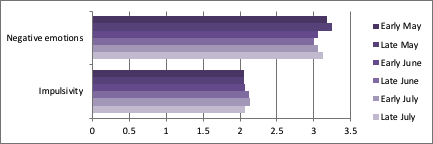

Finally, the surveys from May and June indicated a significant decrease in negative emotions resulting from the COVID-19, in line with the decreasing threat perceptions. Relative to June, negative emotions significantly increased again during the month of July. Levels of impulse control among Dutch citizens did not change from early May to late July.

More lenient restrictions and increasing infections: which resources sustained compliance in July?

In sum, our findings suggest that relative to May and June, compliance with safe-distance measures has ceased to erode during the month of July. At the same time, some of the key resources that sustain compliance have stabilized, or even have recovered (e.g., capacity to comply with safe-distance measures, substantive support for such measures, perceived threat of the virus). Which processes explain whether Dutch citizens complied with safe-distance measures during this period? To answer this question, we conducted linear regression analyses, in which the various resources that we have measured were used to predict participants’ compliance. To illustrate how these processes have evolved during this month, we contrast them with those that explained compliance in May and June. This comparison illuminates whether the processes that explain compliance have changed now that COVID-19 infections are again on the rise, while mitigation measures have further been reduced in scope.

Factors predicting compliance with mitigation measures, early May – late July.

| Early May | Late May | Early June | Late June | Early July | Late July | |

| Independent variables | ||||||

| Capacity to comply | ||||||

| Practical capacity to comply | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Knowledge of measures | + | |||||

| Clarity of measures | + | |||||

| Impulsivity | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Opportunity to violate | – | – | – | – | ||

| Substantive support | ||||||

| Moral alignment | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Authority response | – | – | – | |||

| Negative emotions | + | + | + | |||

| Obligation to obey the law | ||||||

| Normative obligation | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Non-normative obligation | – | |||||

| Rule orientation | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Costs and benefits | ||||||

| Costs of compliance | + | |||||

| Perceived health threat | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Deterrence | ||||||

| Punishment certainty | + | |||||

| Punishment severity | ||||||

| Procedural justice of enforcement | + | |||||

| Descriptive social norms | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Age | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Gender (control variable in May and June surveys only) | + | + | + | + | ||

| Education | + | + | + | + | ||

| Care professionally for COVID patients | – | – | – | |||

| Health issues placing oneself at risk | + | |||||

| Health issues placing others at risk (control variable in July surveys only) | ||||||

| Trust in science | ||||||

| Trust in media (control variable in June and July surveys only) | – | |||||

| Political orientation conservative (control variable in May and July surveys only) | ||||||

| Political orientation undisclosed (control variable in May and July surveys only) | – | |||||

| Socio-economic status change (control variable in July surveys only) |

The results largely confirm the patters that were observed in our surveys in May and June: for the most, the resources that fueled compliance in May and June continue to do so in July. Dutch citizens complied more with COVID-19 mitigation measures if they had greater practical capacity to keep at a safe distance from others. They also complied more the more threatening they regarded the virus, and the more negative emotions they experienced over it. Compliance was also greater the more they morally believed that people should keep a safe distance from others (moral alignment), the more they themselves felt morally obliged to (unquestioningly) obey (normative obligation), and the more they were inclined to obey legal rules in general (rule orientation, early July only). They also complied more the more they perceived that others in their social environment were complying.

There also were factors that undermined compliance. In July, as in May and June, impulsive persons were less likely to comply. Compliance was also lower among people who saw more opportunities for violating safe-distance measures. And, people who evaluated the authority response to COVID-19 more favorably were themselves less likely to comply (in early July), as were people who only obey the authorities out of fear (non-normative obligation, in late July).

Understanding compliance from the “intelligent lockdown” to the “1.5 meter society”, early May-late July

When we consider the period from early May to late July, then the results make clear that five resources consistently increased compliance with safe-distance measures: greater perceived threat of the virus, greater moral alignment with the measures to counter it, greater capacity to comply with those measures, social norms that support compliance, and better impulse control. Also, greater moral obligation to obey the rules, and greater inclination to obey legal rules in general, tended to predict greater compliance.

Less consistent predictors of compliance were perceived opportunities for violating the measures, evaluations of the authority response, and negative emotions. Although significant associations with compliance were observed in several of the surveys, these seem to be less strong or consistent predictors of whether Dutch citizens will comply than those that were mentioned before.

Some factors only predicted compliance in certain surveys, or did not do so at all. There were few indications that Dutch citizens’ willingness to comply was affected by the personal costs of the virus, or by enforcement of the measures (e.g., deterrence, procedural fairness). Also, knowledge and clarity of the measures did not seem to play a major role. It is important to stress that this does not mean that these factors are wholly unimportant to compliance: rather, these findings show that in context of the Netherlands, during the period on which our surveys have focused, and when focusing solely on safe-distance measures, these perceptions were not related to compliance. This does not negate the possibility that they may be influential in different contexts (e.g., for compliance of stores and restaurants, rather than citizens; in countries where measures are more or less strictly enforced; for those whose personal costs are not limited by social welfare).

Keeping COVID-19 at bay

Since the month of July, COVID-19 infections in the Netherlands have been rising again. The findings from our surveys suggest that during this period, Dutch citizens’ compliance with safe-distance measures has partially recovered, as have important resources that enable this. Importantly, this has occurred in spite of further relaxations to prior, more restrictive mitigation measures. What does this teach us about compliance with safe-distance measures, and ways in which policy can improve this?

The finding that compliance increased while measures were relaxed underlines that in the context of the Netherlands, restrictive measures and deterrence do not seem to play a major role in promoting compliance. This is in line with the idea that the Netherlands mostly has refrained from strongly restrictive measures, such as lockdowns or stay-at-home orders. Nevertheless, it does not seem to be the case that the further opening of society has hurt (reported) compliance with safe-distance measures during this period (although it is possible that such an impact is hidden by other developments).

The finding that compliance is resuming at a time when infections are on the rise seems to highlight the role of threat perceptions. Perceptions of the threat of the virus had steadily reduced from May to June, in line with the falling rate of infections. It appears that as infections have rebounded, so have flagging perceptions of the threat of the virus – which according to our analyses, contribute importantly to compliance. It is also likely that such perceptions are closely connected to citizens’ substantive support for mitigation measures, and their felt obligation to obey them – which also are important predictors of compliance. It appears that these resources are more easily mobilized in instances when infections are on the rise than when they are receding, and the threat of the virus, and support for the measures, appear to dissolve. A crucial challenge for authorities in the Netherlands (and elsewhere) therefore is to keep alive the continued threat of the virus, to conserve citizens’ support during periods when the virus is receding. Whether the Dutch government’s approach (appealing to citizenship, social norms, and solidarity with vulnerable others) will be sufficient for this purpose remains to be seen.

In step with these developments, the month of July also spelt an end to the gradual decline in Dutch citizens’ capacity to comply with safe-distance measures. Their decreasing capacity may reflect many things, including more crowded environments, but also the return to physical workplaces where it is more difficult to keep distance from others. The notion that this decline has halted is important for compliance, as citizens’ capacity was a powerful predictor of compliance throughout. This finding also underlines, however, that authorities can bolster compliance with safe-distance measures by measures that increase citizens’ capacity, or remove their opportunities to violate. Interventions that increase the capacity of citizens to comply with safe-distance measures can contribute to their awareness of the measures (e.g., social distancing applications), or fundamentally decrease the frequency that they come into close contact with others (e.g., distance work, e-learning). This also applies for interventions that remove opportunities to violate (e.g., contact-minimizing layouts), which make it physically impossible (or more difficult) to come close to others. The downside of such measures, of course, is that they go at the expense of individual choice and freedom.

Although several resources seem to have stabilized or been replenished with the resurge of infections, social norms toward safe distancing have continued to erode. In part, this finding may reflect the fact that over the past period, environments have become more crowded again, or are inherently unsuited to keeping distance from others. Nevertheless, it is important to stress that this can be an important threat to compliance. As our analyses show, when people perceive fewer others as complying with safe-distance measures, they themselves are also less likely to comply. For this reason, the notion that norms toward compliance continue to erode is an important cause of concern. Possibly, this trend will be reversed by the increasing threat perceptions, and by rising support for the measures, which may alter social norms by leading more people to comply. At the same time, however, it is clear that there can be considerable differences between people’s attitudes toward the measures and their actual tendency to comply, especially when few others do so. It is poignant, therefore, that the Dutch government continues to maintain that compliance is the norm (although whether this is effective is questionable when this differs from what people see in the streets). An important means by which such social norms can be instilled is by using measures that change the environment such that compliance becomes the default. A case in point are the measures to facilitate working from home, which were implemented by the Dutch government at the onset of the COVID crisis. Working from home not only enabled many Dutch citizens to remain at a safe distance from others, it also meant that most others in one’s environment were complying with the measures (i.e., compliance was the descriptive social norm). The use of interventions that increase citizens’ capacity to comply, or remove their opportunities to violate, therefore may not only be directly effective, but also indirectly, by changing social norms that can fuel compliance.

At present, it is unclear whether compliance in the Netherlands will continue its present trajectory, and how the approach that the country has chosen will develop in the future. For this reason, we will continue to monitor these processes in future surveys – to further unravel what explains compliance with mitigation measures, and how this can be utilized in effective policy.