Since the end of March 2020, the Netherlands has been under social distancing and lockdown measures to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 Coronavirus. We studied to what extent Dutch citizens complied with these measures in the period between 7 and 14 April, when they had just been implemented. How has their compliance with these measures developed in the month of May? To study this question, we conducted two additional surveys, on May 8-14 and on May 22-26.

The April survey indicated that Dutch citizens were displaying considerable levels of (self-reported) compliance with social distancing and lockdown measures. It also revealed several factors that explained why they complied. Citizens reported more compliance if they morally agreed with the measures, were practically able to comply with them, and were confronted with less opportunities for violating them. Also, citizens reported more compliance if they had better knowledge of the measures, and if they regarded the pandemic as a serious threat. Conversely, impulsive citizens were less likely to report that they had complied with the measures.

During the month of May, the lockdown measures were lifted, such that Dutch citizens were allowed to leave their household for work and other activities. Nevertheless, other mitigation measures for COVID-19 remained in place, particularly social distancing. Under these measures, citizens are obliged to keep a safe distance (1.5 meters or more) from others. These more lenient mitigation measures have provided Dutch citizens with more freedom of movement. At the same time, however, they also produce other, more undesirable effects: greater proximity to others; more opportunities for getting close to them (in violation of social distancing measures), and more difficulty for authorities to monitor this, to name just a few. As such, it is important to understand how these processes have developed during the month of May. To this end, we collected two additional surveys within this period. In these surveys, we assessed citizens’ (self-reported) compliance with COVID-19 mitigation measures, as well as the various processes that we used to explain this in the survey in April.

Evolution of compliance in the month of May

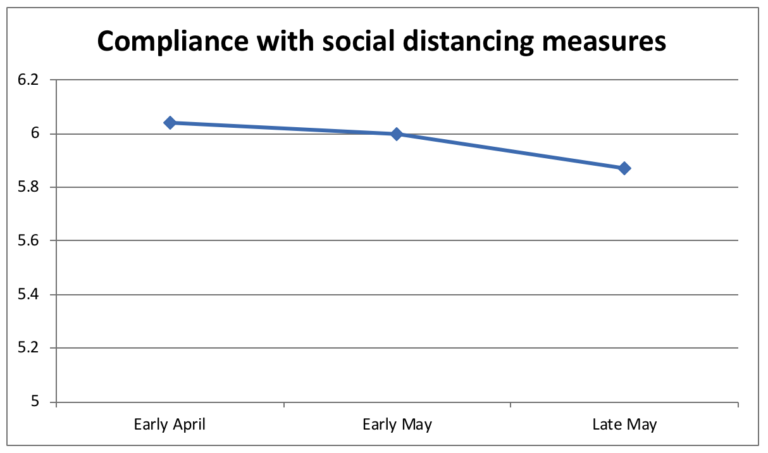

We conducted two surveys in representative samples of Dutch citizens, collected via the research panel StemPunt.nu. The first survey (N = 984) was conducted between May 8-14, the second (N = 1021) between May 22-26. As noted, prior to this period, lockdown measures were repealed within the Netherlands. As such, the new surveys focused exclusively on compliance with social distancing measures (in contrast to the April survey, which also examined compliance with lockdown measures). Survey participants were asked to what extent they kept a safe distance (1.5 meters or more) from others (e.g., from people from outside of their household, from colleagues at work, etc.), and to what extent they did so during various activities (e.g., when walking or exercising, while grocery shopping, etc.). We compared reported compliance across these situations between late May and early May, as well as comparing this to compliance with social distancing measures in the April survey (exploratively, as it utilized a less refined measure).

From early to late May, a slight (but statistically significant) decline in self-reported compliance with social distancing measures was observed. Dutch citizens therefore seem to comply somewhat less with these measures than before, although compliance remains relatively high in absolute terms.

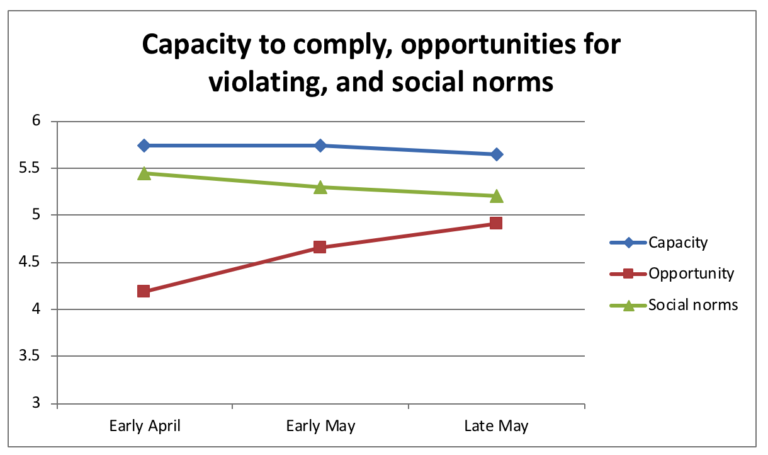

There are several other discrepancies between early and late May that seem to support this decline. To begin with, let’s consider respondents’ capacity to comply with social distancing measures, their opportunities for violating them, and social norms with regard to complying with social distancing measures.

During the course of May, Dutch citizens still reported having considerable capacity to obey COVID-19 mitigation measures (e.g., being able to keep a safe distance from others at work, when walking or exercising, while grocery shopping, etc.) Nevertheless, a small (but statistically significant) decline in capacity was observed in late May. Similarly, throughout May, Dutch citizens reported increasing opportunities for violating social distancing measures. These observations are in line with the idea that more people leaving their household (and are doing so more frequently), and thereby are finding it harder to keep a safe distance from others (unwillingly or otherwise). This is also suggested by the finding that norms for compliance within their network seemed to decrease at the end of May (again, a decrease that is small, yet statistically significant).

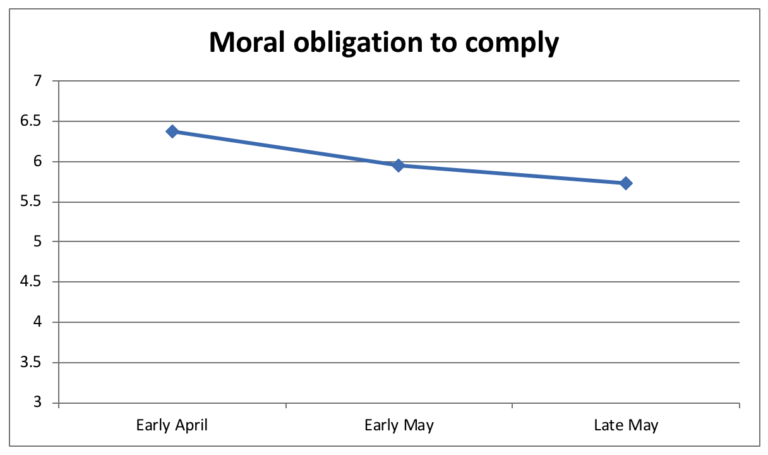

In addition to practical capacity and opportunities, there also are indications that the support of Dutch citizens for social distancing measures are slowly (but meaningfully) declining.

From early to late May, Dutch citizens showed a decrease in reported moral obligation to follow COVID-19 mitigation measures. Although their obligation to do so remains relatively high in absolute terms, this pattern nevertheless suggests that the perceived obligation of Dutch citizens to unquestioningly follow government measures is slowly declining.

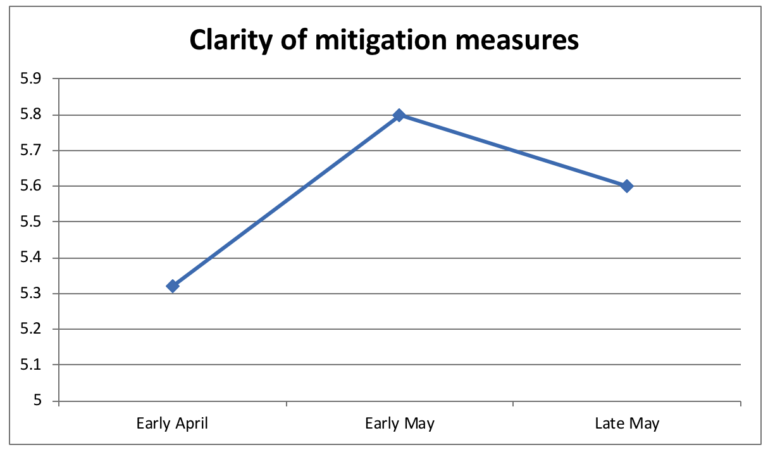

Perhaps most telling are citizens’ impressions of the clarity of the measures taken to control the COVID-19 epidemic.

Relative to April, Dutch citizens firstly reported that the government’s mitigation measures were more clear to them in early May. In late May, however, we again observe a (statistically significant) decrease in reported clarity. Apparently, as the Netherlands are moving out of the lockdown and “normal” life is recommencing, citizens also find the government’s measures less clear. This may reflect the impression that measures to practice social distancing seem incompatible with recommendations to resume work, education, and leisure activities, or are difficult to implement in practice.

To put these observations into perspective, it is firstly important no note that Dutch citizens’ self-reported compliance with mitigation measures continues to be high in absolute terms. This also applies for their practical capacity to comply, their support for these measures, and social norms regarding distancing. And although the perceived clarity of these measures has decreased towards the end of May, this also remains relatively high in absolute terms. This is perhaps reassuring: although lockdown measures have been repealed within the Netherlands, and although “normal” life is resuming, this does not seem to have greatly diminished these resources. Nevertheless, the small, but significant decreases that occurred in May do raise some concern. The reason for this is that several of these resources (e.g., citizens’ capacity to comply, their support for mitigation measures, etc.) were important predictors of compliance in our previous survey. Could that mean that the basis of compliance is slowly eroding?

Which factors contributed to Dutch citizens’ compliance with mitigation measures in May?

To understand this question, it is necessary to examine which factors contributed to Dutch citizens’ compliance with mitigation measures during the month of May. To answer this question, we conducted linear regression analyses, in which various features of the participants and their social environment were used to predict their compliance with social distancing measures. To illustrate how these processes have evolved during this month, we contrast them with those that explained compliance with mitigation measures in April. This comparison illuminates whether the processes that explain compliance have changed now that the scope of the measures has been reduced. Do note that compliance therefore refers to different behaviors (i.e., following social distancing and lockdown measures in April; following social distancing measures in May). Moreover, the analyses of the April survey have been revised for comparability with the May survey (i.e., corona care, trust in science and knowledge of mitigation measures are treated as covariates, rather than predictors or selection criteria).

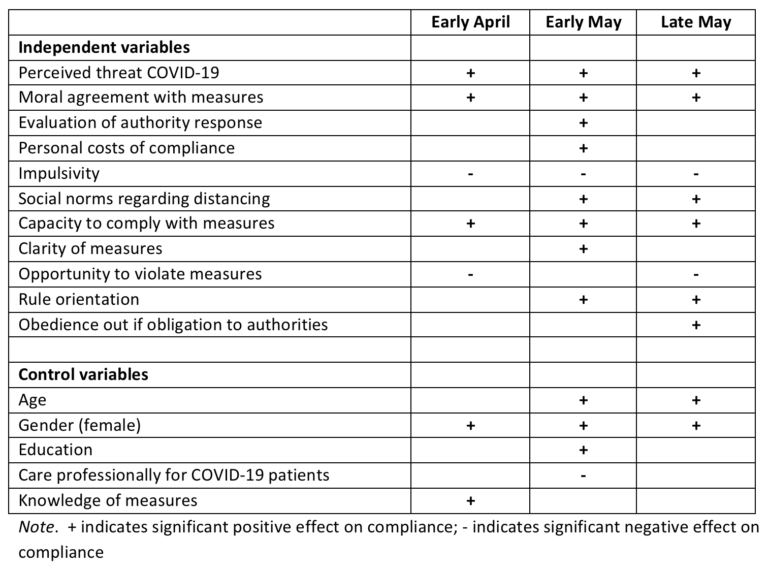

Table 1: Factors predicting compliance with mitigation measures in early April, early May, and late May.

The results of both analyses are displayed in Table 1. They show that the factors that predict compliance for the most are highly similar across the three time points. People complied more if they had greater practical capacity to keep at a safe distance from others. Also, people who agreed more with the measures complied more. And, people who perceived the COVID-19 epidemic as more threatening engaged in more social distancing. Impulsive persons, on the other hand, were less inclined to do so.

There were also some factors that consistently predicted compliance in May, but did not do so in the April survey. Compliance was higher for people who generally feel a greater obligation to obey legal rules (rule orientation). Also, people also complied more if they perceived that others in their social environment engaged in social distancing. It is possible that these findings reflect that intrinsic motives and norms became more influential as lockdown measures were repealed in the Netherlands. Whether this may indeed be the case is too soon to tell, due to differences between the sample composition (younger in April) and the measurement of these concepts (more refined in the May surveys).

In addition to these, there were some factors that inconsistently predicted. For example, people complied less if they reported greater opportunity to violate social distancing measures, but this was statistically significant only in the surveys in early April survey and late May. Other factors only predicted compliance in a single time period (e.g., personal costs, clarity of measures, obligation to unquestioningly follow the decisions of the authorities). It remains to be seen whether these are isolated cases or represent processes that are more meaningfully related to compliance. If so, they should persist, and maybe become more influential in the future, as further restrictive measures are loosened.

Mitigating COVID-19 in an open society

For the most, the findings from May indicate that the ingredients for compliance within the Netherlands were similar to those observed in the previous period, in April: practical capacities for social distancing, and (to a lesser extent) opportunities for not doing so; personal factors such as one’s orientation toward the epidemic, the measures, and legal rules in general, and impulsivity. But although the resources that enable compliance are similar, their supply is threatened. The loosening of mitigation measures within the Netherlands is slowly, but significantly eroding support for firm measures. Simultaneously, the return to “normal” life is slowly eroding people’s capacity to socially distance, and presenting them with more opportunities for not doing so.

Although it is likely that these resources will continue to foster compliance in the future, it is likely that they will be in shorter supply as mitigation measures are further loosened. To the extent that these processes erode social distancing, this may open the door for a resurge of infections. It is also possible, however, that new processes may come to the fore, or that new developments will strengthen our resources for compliance – such as the introduction of technological aids (e.g., social distancing applications), or innovations in the arrangement of work, education, and the physical environment (e.g., distance work, e-learning, contact-minimizing layouts). For this reason, our research will continue to monitor these developments across the upcoming months.